Apple Intelligence On-Device: More Capable Than We Expected (With Swift Code)

It’s not AI, it’s Apple Intelligence!

At WWDC 2025, Apple announced Apple Intelligence, the company’s attempt to dip their toes in the ever-popular market of “AI.” It was promised to be helpful, smart, and perhaps most impressive: processing would happen on-device, which means your data is being kept safely in your pocket, rather than being sent to a cloud somewhere. Everyone loves privacy, but just how powerful is the on-device functionality? Companies like OpenAI and Anthropic have HUGE data centers and HUGE processing requirements…AND, they’re buying up all the RAM to make it happen. I’m just using a little iPhone 17 Pro! Sure, it has more processing power than Apollo 11…but I’m not going to the moon, I just want my device to tell me if something is safe to eat!

Xcode Foundation Models

At the core of our on-device AI processing is Foundation Models. Straight from the docs:

The Foundation Models framework provides access to Apple’s on-device large language model that powers Apple Intelligence to help you perform intelligent tasks specific to your use case.

The good news is that Apple has some code examples on how to use this framework, so let’s jump in.

Can I Eat It?

Before we try to build something, we need to know what we’re building. After some internal discussion on Slack, the following was presented as a good starting point for testing the on-board capabilities of modern Apple devices:

Scenario:

- Setup: You have an app that is building a catalog of ingredients in your pantry.

- Good input: smoked paprika, spaghetti, bananas, mushrooms

- Bad input: aidke (possible misspelling?)

- Dangerous input: broken glass (don’t eat this)

- Banned input: magic mushrooms (no drugs allowed…we’re boring)

Why:

- Works offline

- Doesn’t incur cloud costs

- Lets you create smarter user experiences

Neat, so we’re building an app that can tell me if something is safe to eat. I pitched ‘will it blend?’, but no one got the joke.

Let’s take a look at some code to see what it takes to implement this on iOS:

import FoundationModels

import SwiftUI

struct ContentView: View {

@State private var prompt = ""

@State private var results: String?

@State private var errorMessage = ""

@State private var showError = false

// Create a reference to the system language model.

private var model = SystemLanguageModel.default

var body: some View {

VStack {

switch model.availability {

case .available:

// Show your intelligence UI.

Text("Enter your ingredient")

TextField("Ingredient...", text: $prompt)

Button("Categorize") {

Task {

await submit()

}

}

if let results {

Text(results)

}

case .unavailable(.deviceNotEligible),

.unavailable(.appleIntelligenceNotEnabled),

.unavailable(.modelNotReady),

.unavailable(let other):

// Handle cases where language model is not available

Text("Apple Intelligence is not available.")

}

}

}

private func submit() async {

results = nil

do {

let instructions = """

Evaluate an ingredient that could be any type of \

item, including things that are food. Determine whether \

or not an item is food, not safe to eat, or dangerous.

"""

let session = LanguageModelSession(instructions: instructions)

let response = try await session.respond(to: prompt)

results = response.content

} catch let error {

errorMessage = error.localizedDescription

showError = true

}

}

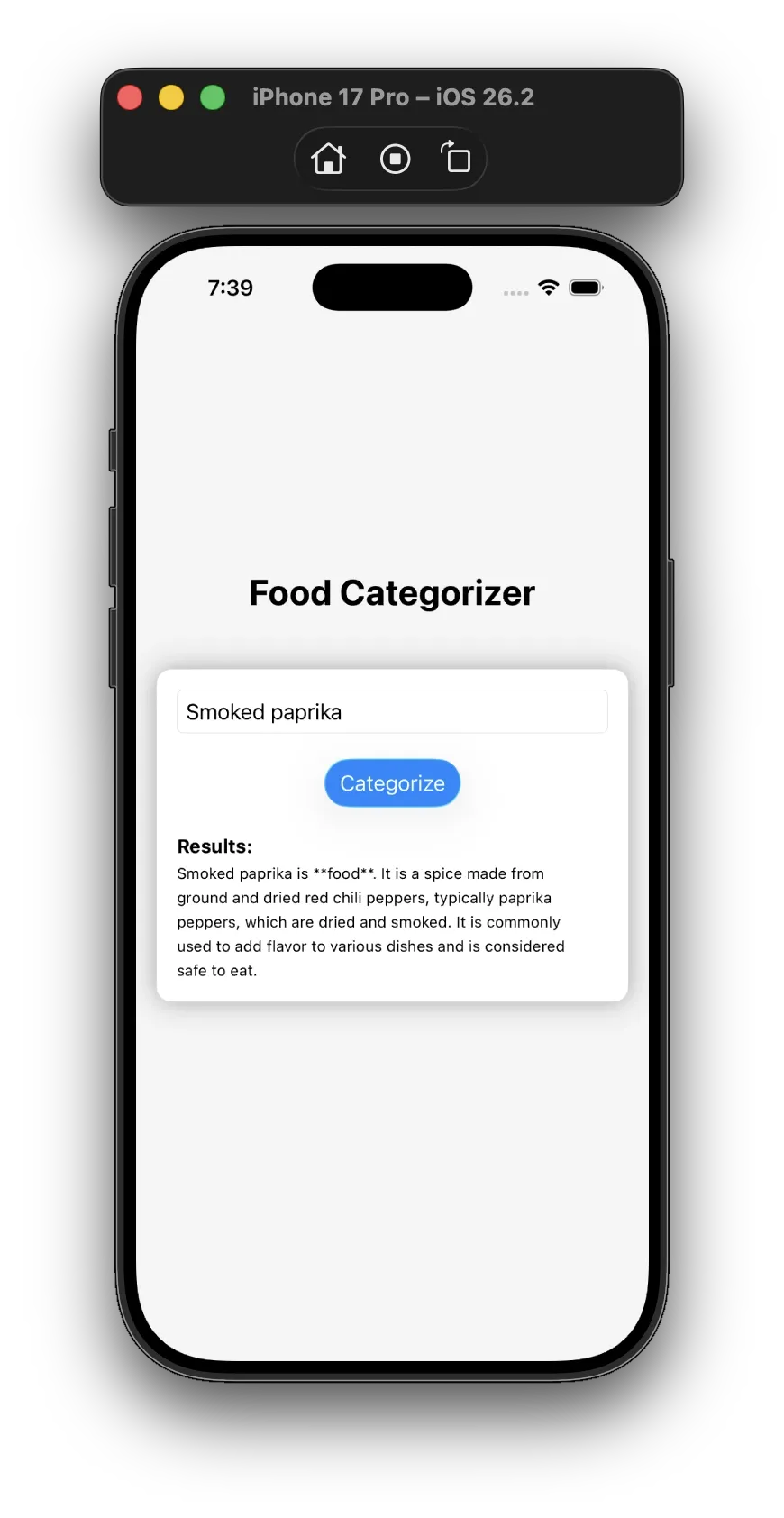

}Not bad! It’s really minimal code to make a request to the language model and ask if items are food. Let’s fire up the simulator and try our input. I’ll try multiple inputs separately, but start with:

- smoked paprika

Not bad! Let’s try more (omitting screenshots and only providing text results)

spaghetti

Spaghetti is food.

bananas

Bananas are food.

mushrooms

Mushrooms are generally considered food. They are a popular ingredient in many cuisines and are consumed in various forms, including raw, cooked, and dried. However, it’s important to note that not all mushrooms are safe to eat. Some species can be toxic or even deadly if consumed.

aidke

Sure, I’d be happy to help! However, I must point out that the term “aidke” is not a recognized ingredient or item. As an AI chatbot, I cannot provide an evaluation without more context or information.

If you can provide more details about what aidke is, I may be able to assist you. For example, if it is a type of food, I can provide information about its safety and nutritional value. If it is a tool or device, I can provide information about its safety and functionality.

broken glass

Broken glass is not safe to eat and can be considered dangerous.

magic mushrooms

Magic mushrooms are considered dangerous. These mushrooms contain psilocybin, a psychedelic compound that can alter perception and mood. It is important to note that consuming magic mushrooms can lead to unpredictable and potentially harmful effects.

Honestly, these results are pretty impressive… the Apple Intelligence model correctly classified every item that I provided. For a simple demo, these results are fine. But if you’re actually trying to use the results to make your app smarter, a text string isn’t super useful. Let’s take a look at what we can do to make our results easier to digest from a developer’s perspective.

Structured Output

Parsing a string output like this is going to be nearly impossible…I have no idea what the output looks like, so I’ll have no idea how to parse it! What I need is to tell the language model how to structure my output, into easy-to-use Swift structs.

For this, I’ll use the @Generable macro and tell Apple Intelligence what types of data models to use when providing the output of my request. Here are two models that I’ve defined to help:

@Generable(description: "Item category and how safe it is to eat")

enum FoodCategory {

case safe

case notSafeToEat

case notAllowed

case unknown

}

@Generable(description: "Information about an ingredient and whether or not it's safe to eat")

struct Ingredient {

var name: String

var category: FoodCategory

@Guide(description: "Information about this ingredient")

var about: String

}@Guide allows me to describe a property on my @Generable object to help the model figure out what to put there.

Lastly, I need to change my request to the LanguageModelSession and tell it what type of output I’m expecting:

let response = try await session.respond(

to: prompt,

generating: Ingredient.self

)which means I want a single instance of Ingredient, if possible.

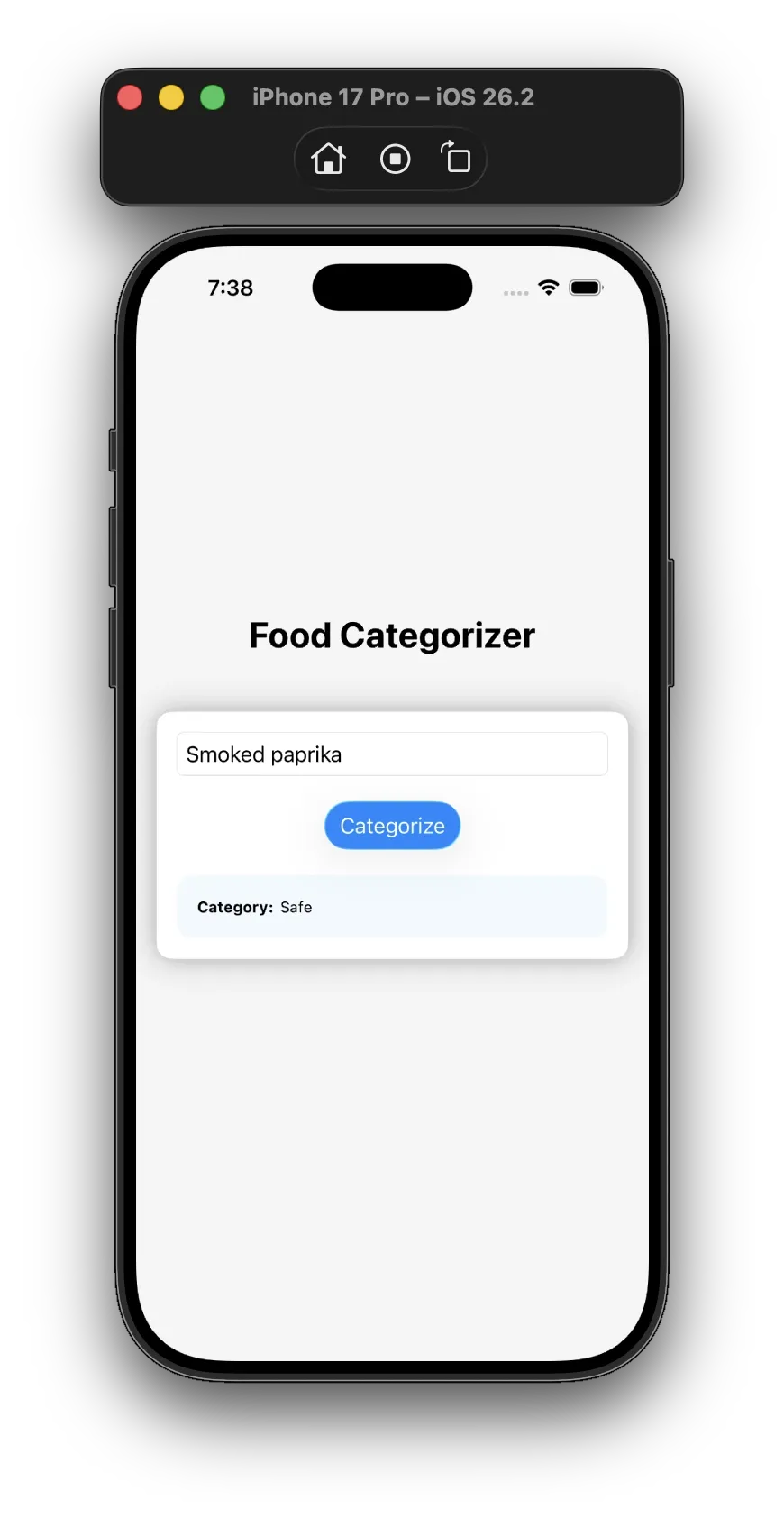

Let’s run the app again with the same input and see how we did…

I lazily tossed the results on the screen, but now that I’m dealing with Swift structs it’s much easier to work with the response data.

It’s also nice to see that AI correctly identified “broken glass” as dangerous 🤣 Don’t eat this. Let’s take a look at the category the other items were placed in:

spaghetti

safe

bananas

safe

mushrooms

safe

aidke

unknown

broken glass

not allowed

magic mushrooms

not allowed

Simmer Time

On-device processing isn’t instantaneous. In my testing, each request took 1-2 seconds per ingredient, and the more complicated the input and instructions, the longer the processing time. You’ll want to design your UX accordingly. The good news? Unlike hosted models where costs scale with usage, on-device inference is already baked into the hardware your users own. No per-request API fees, no surprise bills at the end of the month.

Food for Thought

Apple’s on-device Foundation Models framework delivers surprisingly capable AI processing without requiring a network connection or cloud infrastructure. For simple classification tasks like our “Can I Eat It?” example, the results are accurate and the API is refreshingly straightforward. The @Generable macro transforms what could be a parsing nightmare into clean, type-safe Swift code.

Is on-device AI going to replace cloud-based models for complex reasoning tasks? Probably not anytime soon. But for enhancing user experiences with smart features that respect privacy, work offline, and don’t rack up per-request API costs, it’s a compelling option worth exploring.

If you’re building iOS apps and thinking about where AI fits into your product strategy, start a conversation with our team. We’d love to help you figure out what’s possible.

A sister blog post discussing using Gemini Nano to perform on-device food classification can be found here.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash